In mid-June, the City of Denver confirmed the presence of the emerald ash borer (EAB)…

Trouble with trivets: Art projects can carry emerald ash borer

DENVER — When you hear stories of how harmful, invasive pests are transferred from Point A to Point B, the movement is often attributed to the irresponsible actions of an unwitting human. But the truth is usually far less black and white — at least that’s what Sara Davis, program manager with Denver’s Office of the City Forester, realized earlier this year.

Davis is one of the leaders of the Be A Smart Ash campaign, which aims to prepare Denver and educate residents ahead of the inevitable arrival of the emerald ash borer (EAB), an invasive pest that has wiped out ash tree populations in 26 states as well as in Canada.

EAB was discovered in Boulder in 2013 and in neighboring Longmont in early June. And at a Denver Botanic Gardens event she recently attended on behalf of the Be a Smart Ash campaign, Davis feared EAB had made its way to the Mile High City.

Interestingly enough, that bad feeling in the pit of her stomach came as she peered out on the dessert table.

“I noticed the caterers were moving plates around using wooden trivets,” Davis said. “I turned to my colleague and said, ‘Is that a piece of ash?’”

Sure enough, the trivets were made from ash trees. Not only that, they displayed tell-tale signs of EAB infestation, including wavy trail lines in the bark.

“I went up to the caterer and said, ‘I’m going to be taking this,’” Davis recalls. She can laugh now because of what she uncovered after several days of investigating — the key word being “several.”

The first few days were tense, as Davis worked with the caterer to track down where the trivets had originated. Sure enough, they were brought to Colorado by an out-of-state couple hosting a do-it-yourself wedding in Larkspur, Colo. The resourceful couple, simply trying to save a few bucks and add a personal touch to their big day, carved the trivets from dead ash trees in their front yard in Lake Forest, Ill., which happens to be in the heart of an EAB infestation zone.

The good news? The trees had been dead for several years before they were transported.

“It was clear there was no live EAB larvae in the trivets at the time they were moved,” Davis said.

But the innocence of the whole incident got Davis thinking.

“It was so funny,” she said. “We always say, ‘Don’t move firewood.’ But this wasn’t firewood; it was a Pinterest idea. You never expect wood to move around like that.”

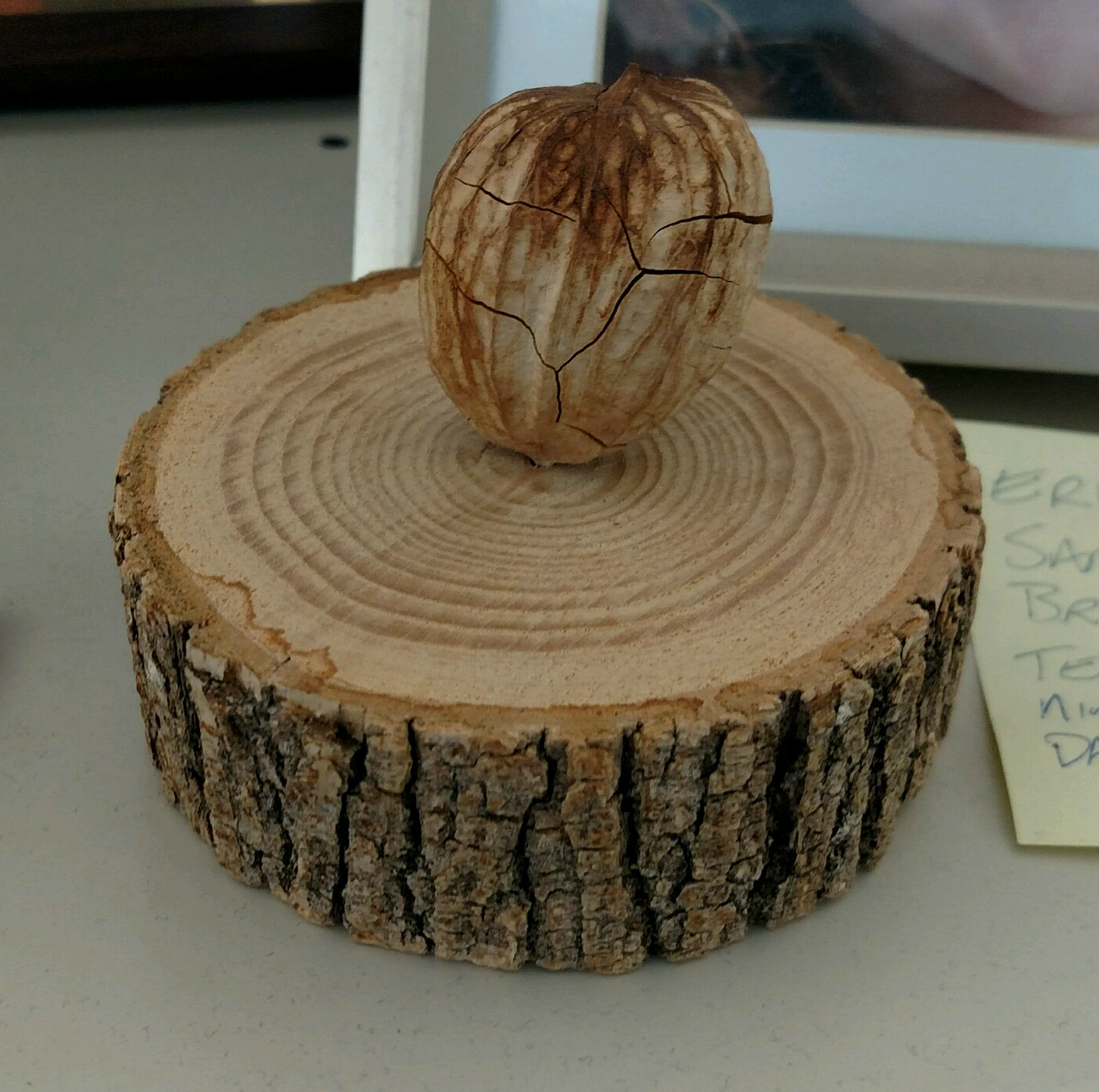

Yet after the trivet ordeal, Davis started seeing these troubling, traveling, wood-based art projects everywhere — her own desk included.

The thank-you note she received from colleagues after her office hosted the 2015 Partners in Community Forestry Conference was sent on a slice of wood that fellow foresters had signed with a Sharpie. At a meeting with a group of outdoor enthusiasts, Davis noticed the coasters in their office were made of tiny chunks of wood.

Back in her own office, she noticed a tiny stump her coworkers had brought her from a hike. Examining it more closely, Davis marveled, “There’s still lichen on this wood.”

It all served as a good reminder, and perhaps a new cautionary narrative on the movement of invasive pests: Anyone can do it — even those who fight these tree-threatening pests for a living.

So what can you do to prevent it? The safest thing, Davis said, is to not transport wood yourself – ash or otherwise. Period.

“If you do need to transport wood for whatever reason, make sure it comes from a reputable supplier,” Davis said.

Have more questions about when it is and isn’t OK to transport wood? Visit our friends at Don’tMoveFirewood.org